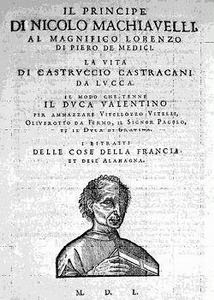

I've had this sitting on my shelf for a while and never really gotten around to reading it until now. Honestly, I wish I'd sat down and read it before because this book is an absolute masterpiece. But first a little bit of background. The author of this work is one Niccolo Machiavelli, a Florentine diplomat and politician from the fifteenth century, born in 1469 and contemporary to such Renaissance greats as Lorenzo de Medici, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (more on him soon!) and Cesare Borgia. The Prince is a political treatise written by Machiavelli in around 1513 after his imprisonment and torture, which he began when he went into retirement at his farm near San Casciano. Shortly after his retirement here, in around 1520 he was commissioned to write a history of Florence by Cardinal Giovanni de Medici (later Pope Leo X) which was finished in 1525. Machiavelli died shortly after this, after a very brief return to public life, in 1527.

And so to this extraordinary work. I will be clear from the outset, The Prince is certainly not all kittens and rainbows. Far from it. It is in fact an essay on how a Prince should act to gain loyalty and keep it. He lists all the good points that Prince must have to gain his loyalty but then turns around and gives a list of points when a Prince must resort to cruelty to keep said loyalty; and he gives examples of both past and present (at least his contemporary) rulers and princes to back these points up. When this treatise was published (at least in the Penguin Classics version) it includes a letter of dedication to Lorenzo De Medici, aka "Il Magnifico" which states that:

"So, Your Magnificence, take this little gift in the spirit of which I send it; and if you read and consider it diligently, you will discover in it my urgent wish that you reach the eminence that fortune and your other qualities promise you."

When I read the Penguin Classics copy, I wondered how on earth Lorenzo could have dedicated the book to Lorenzo. Lorenzo de Medici when the man died in 1492. This comes across as a printing mistake, and it is more likely that Machiavelli dedicated it to Lorenzo de Piero de Medici, Pope Leo X's nephew and grandson of Lorenzo the Magnifence.

The book itself, as previously mentioned is his summary of how Princes can gain and keep their power. And the great thing about this book is that Machiavelli bases his treatise on first hand experience. Many of his contemporary examples come from men who he has met in his own life and there is one man who crops up time and time again:

Cesare Borgia.

Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI, would have been a well known entity to Machiavelli. During his life time, Machiavelli met and dealt with Cesare on many occasions and, it seems to me at the very least, held a hell of a lot of respect for Cesare Borgia. Machiavelli mentions Cesare at many points during his work and uses his example to justify his points. And throughout his work he makes the point that it is better for a man to be a risk taker to gain popularity, and also that if popularity is not gained then he should be a risk taker to remain respect. Cesare is used throughout the work to make this point.

"I will never fear to cite Cesare Borgia and his actions. The duke entered Romagna with auxiliary arms, leading wholly French troops, and with these he took Imola and Forlì. But, such arms not seeming secure to him, he turned to the mercenary ones, judging that there be less danger in them, and engaged both the Orsini and the Vitelli. Later, managing and finding them doubtful, unfaithful, and dangerous, he extinguished them and turned to his own. And one can easily see the difference between these arms, considering the difference between the duke's reputation, when he had only the French and when he had Orsini and Vitelli, and when he was left with his own soldiers and on his own: and always one will find it increased; never was he so esteemed as when everyone saw that he was the total owner of his arms"

Throughout the book you get constant mentions of Cesare and the method of "criminal virtue" that he used to gain his power. Alas, Machiavelli also mentions that Cesare - despite his brilliant methods of gaining and keeping power (such as taking the towns of the Romagna and taking power easily because the people hating their leaders) - failed because of a few very simple reasons; the death of his father Pope Alexander VI, and his trusting in the new Pope Julius II. Such a shame, had Cesare not trusted in Julis then he could have gone on and ruled the Romagna. Alas, his failure lead to his imprisonment and eventual death.

Of course, Machiavelli doesn't always use Cesare's example. Just most of the time. He also uses examples of other Italian rulers such as Caterina Sforza and also rulers from history - listing in turn what they did right and the methods that made them fall. And as I said earlier, he doesn't make it all kittens and rainbows. Oh no, he is really quite blunt with his conclusions. And for that I love him.

There is one other thing I want to mention before I wrap this review up - Machiavelli's "Prince" really did away with the morality of the time and pretty much gave instructions to those from his own time (and ours) of how to gain absolute power. Because of this, the man came to be thought of an an instrument of the devil. When you hear the phrase "Machiavellian tragedy" from Jacobean drama, this is what it points to - someone who endeavours to take absolute power, and because of this the man (despite his brilliance) was for a very long time regarded as an agent of the devil. Reading it myself however, I wonder why people thought this of him because his work makes a lot of sense to me - he recognised the complicated nature of the political life of the time and realised that life wasn't all kittens and rainbows. Machiavelli certainly was a man before his time, and I defy anyone to read this and reject his statements as his words reflect even to our present life.

The man was a genius, despite his own flaws, and his works should in my opinion be read by every one. It really is a masterpiece and a must read for anyone interest in the political happenings of Renaissance Italy.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to both spam and some rather nasty individuals all comments will be moderated.